Beyond the Screen: TV Scenes That Aren’t in Valmiki’s Ramayan

Namaste Shikshanarthis!

The Ramayan is a legendary story that has been retold and reimagined in countless ways. While the Valmiki Ramayan is the earliest written version, many scenes in popular TV adaptations don’t actually appear in Valmiki’s original. This blog takes you on a journey to explore these differences, helping us understand the magic of retelling stories across generations.

Introduction: Why the Ramayan Has So Many Versions

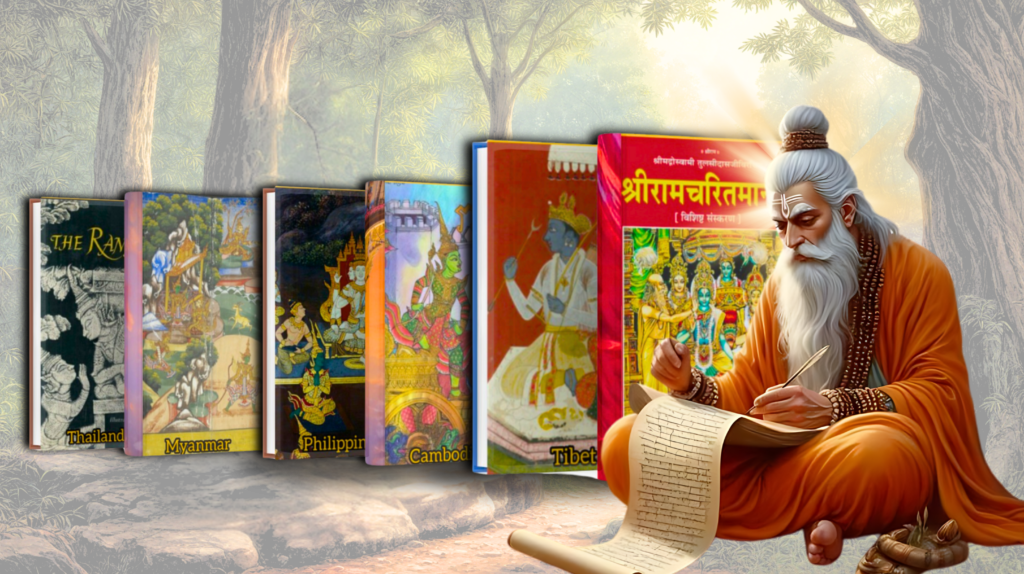

Imagine a story so beloved that it has been retold hundreds of times! That’s the case with the Ramayan. Originally penned by the sage Valmiki, this epic tale of Lord Ram, his beloved Maa Sita, and his loyal companion Hanuman has inspired generations. But did you know that over 300 different versions of the Ramayan exist?

These versions were crafted by poets and storytellers in different languages and regions, like Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas, the Oriya Ramayan, and the Bengali Krittivasi Ramayan. Each storyteller added new scenes, details, and interpretations, allowing each generation to find something special in Ram’s journey. Over time, these unique retellings even found their way into our TV screens and movies, where we sometimes see scenes that are incredibly moving but don’t appear in Valmiki’s original work.

So, in this blog, let’s explore some of the most memorable scenes from TV Ramayans that don’t appear in Valmiki’s Ramayan. Understanding these differences helps us appreciate the story’s evolution and reminds us of how our culture allows stories to grow with us.

The Royal Swayamvar of Maa Sita

One of the grandest scenes in many TV versions of the Ramayan is Maa Sita’s swayamvar, or marriage ceremony. In these shows, kings and princes gather from far and wide, dressed in their finest attire, hoping to win Maa Sita’s hand. It’s depicted as a grand festival with beautiful decorations, music, and a huge audience, much like a royal wedding today. The highlight? Each suitor tries to lift the mighty bow of Lord Shiva, for only the strongest and most worthy prince can win Maa Sita as his bride. Finally, Ram, guided by the sage Vishwamitra, steps forward, lifts, and breaks the bow, winning Maa Sita’s hand.

However, if we look closely at Valmiki’s Ramayan, this scene is quite different. There, King Janak, Maa Sita’s father, is concerned because no suitable match has appeared for his daughter. He decides that anyone who can lift and string the bow of Shiva would prove worthy of marrying Maa Sita. Although many princes come and try, they are unable to lift the bow. When Ram arrives, under Vishwamitra’s guidance, he breaks the bow effortlessly, and Janak immediately agrees to the marriage. Unlike the festive scenes shown in TV serials, this swayamvar wasn’t as grand or elaborate. It was simply a moment of destiny.

This grand portrayal likely comes from Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas and the creative interpretations of TV writers who wanted to highlight the majesty of Maa Sita and Ram’s union for modern viewers. So, while the Valmiki version has a simpler approach, the TV adaptation uses the grandness to capture our hearts.

The Enigmatic Lakshman Rekha

Another powerful scene found in almost every Ramayan retelling is the drawing of the “Lakshman Rekha.” According to popular belief, when Ram is off chasing the golden deer at Maa Sita’s request, Lakshman draws a protective line around the hut to safeguard Maa Sita. He instructs her not to cross it, as doing so could invite danger. But when Maa Sita hears cries for help (which are actually the demon Maricha in disguise), she steps over the line, allowing Ravana, the king of Lanka, to abduct her.

The Lakshman Rekha has become a symbol of protection and boundaries in Indian culture. However, in Valmiki’s Ramayan, there is no mention of Lakshman drawing such a line. After Maa Sita urges Lakshman to go help Ram, he leaves reluctantly, after hearing her harsh words, but without drawing any boundary.

Interestingly, the concept of the Lakshman Rekha appears later in Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas, but not directly in the context of Maa Sita’s abduction. Instead, it is mentioned by Mandodari, Ravana’s wife, in a later part of the story. She reminds Ravana how even the smallest line drawn by Lakshman had once stopped him, suggesting that he should not underestimate Ram and Lakshman’s power. This protective line, though beloved and symbolic, is thus a beautiful addition that doesn’t come from the Valmiki Ramayan but serves to illustrate devotion and duty.

Shabari’s Offering of Tasted Berries

One of the most endearing stories from the Ramayan is that of Shabari, a humble devotee of Ram. In TV adaptations, Shabari is shown tasting berries before offering them to Ram, as she wishes to ensure he only receives the sweetest ones. The image of Shabari, a poor old woman, offering her humble, half-eaten berries to Ram is touching, symbolizing devotion that goes beyond rituals.

However, in Valmiki’s Ramayan, Shabari offers fruits to Ram, but there’s no mention of her tasting them first. In this version, she simply welcomes Ram and Lakshman with an abundance of wild fruits and roots. This act of simple, heartfelt hospitality has captivated people for centuries. The added detail of tasting the berries is likely inspired by the Padma Purana and the Oriya Ramayan, where Shabari’s devotion is highlighted through this extra layer.

This story reminds us that devotion is not about elaborate rituals or expensive offerings but about pure love and intention. Shabari’s humble act, whether or not she tasted the berries first, teaches us that devotion lies in the heart.

The Heartfelt Story of Hanuman’s

Chest-Splitting Devotion

Hanuman, Ram’s devoted follower, has countless stories of his love and loyalty. But one of the most iconic scenes, often depicted in TV serials and images, is when Hanuman tears open his chest to reveal Ram and Maa Sita within. This act of devotion is powerful, showing that his heart and soul belong to them.

Yet, this scene does not appear in Valmiki’s Ramayan. In fact, neither Valmiki’s Ramayan nor Ramcharitmanas includes this moment. Instead, it appears in the Bengali Krittivasi Ramayan, a 15th-century retelling. According to the story, Hanuman receives a pearl necklace from Maa Sita as a gift. Upon receiving it, he examines each pearl and discards them, saying they are worthless because they don’t contain the image of Ram and Maa Sita. When others laugh at him, he opens his chest to show that Ram and Maa Sita truly reside within him.

This story is a vivid reminder of Hanuman’s devotion and the idea that true love knows no bounds. For many, this image of Hanuman is unforgettable, symbolizing loyalty and sacrifice.

What Retelling Teaches Us About Our Heritage

You might wonder why different versions of the Ramayan add or alter scenes. These retellings show us that Hindu epics are not rigid; they’re living stories that adapt to new contexts, interpretations, and generations. Each region has added its unique details, reflecting its people’s culture, values, and beliefs. By incorporating scenes like the Lakshman Rekha or Shabari’s berries, later storytellers brought forth powerful symbols of duty, love, and devotion.

These additions make the Ramayan relatable to people of all backgrounds and allow everyone to find something personally meaningful in the story. The Ramayan’s adaptability is a reminder that while the core of Hindu philosophy is timeless, the stories that convey it can be fluid, meeting people where they are.

Conclusion: Embracing a Rich Cultural Legacy

The Ramayan is much more than a single text, it’s a shared cultural legacy that has shaped India’s values, beliefs, and ideals. The TV scenes that don’t appear in Valmiki’s Ramayan aren’t errors or mistakes; they’re expressions of the epic’s living spirit. Each retelling, each added scene, is a layer that reflects the hearts and minds of its people.

Understanding these differences deepens our connection to this ancient epic. It reminds us that while one version may tell a simpler story, the variations enrich it with new meaning, allowing each generation to discover their own connection with Ram, Maa Sita, and Hanuman. So next time you watch or read a Ramayan adaptation, remember that it’s not just a story, it’s a reflection of the countless lives that have been touched by it.